Model Human Processor

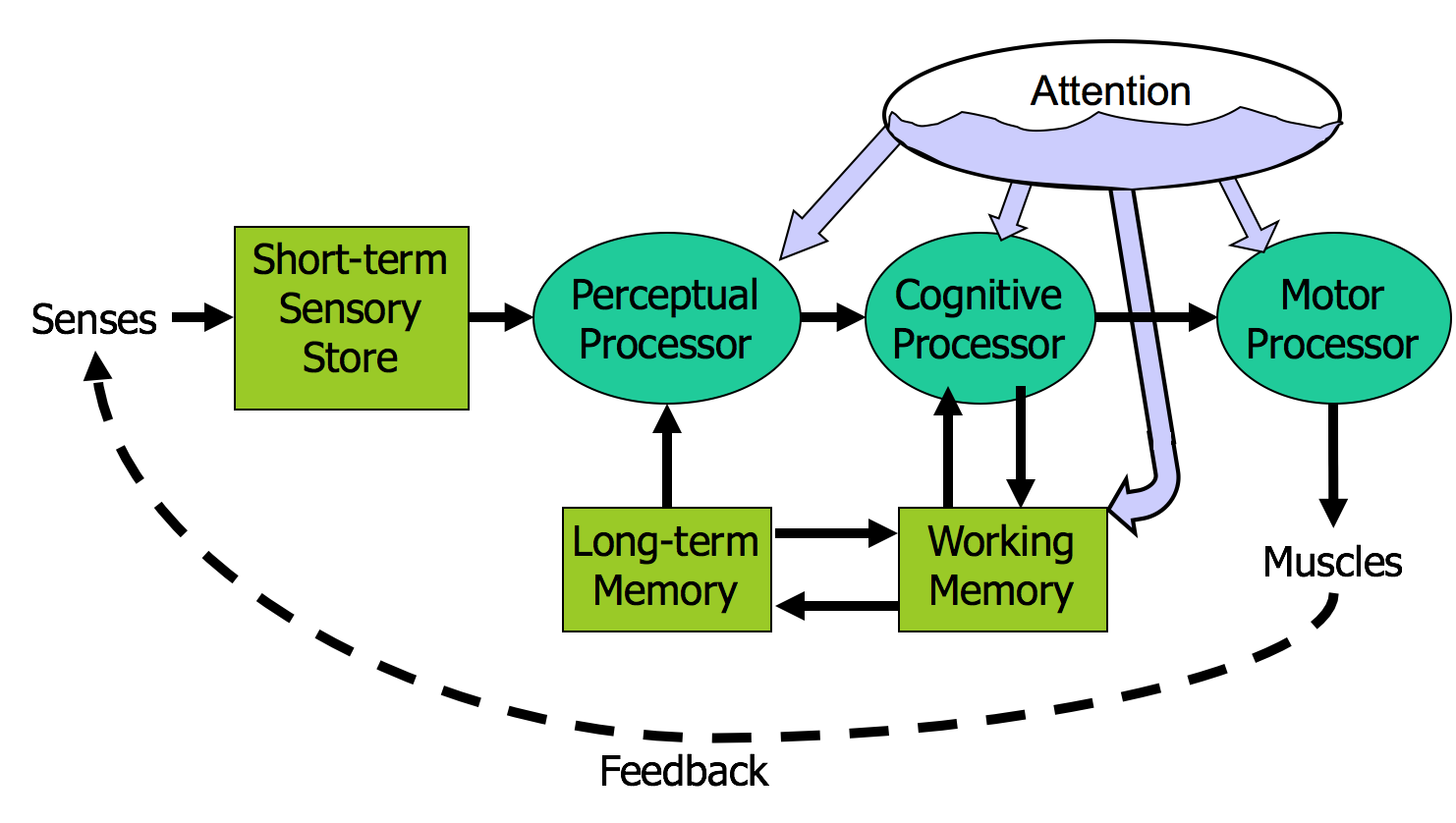

Here’s a high-level look at the cognitive abilities of a human being – really high level, like 30,000 feet. This is a version of the Model Human Processor (MHP), which was developed by Card, Moran, and Newell as a way to summarize decades of psychology research in an engineering model (Card, Moran, Newell, *The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction*, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1983).

This model is different from the original MHP; we’ve modified it to include a component representing the human’s attention resources (Wickens, *Engineering Psychology and Human Performance*, Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, 1984).

This model is an abstraction, of course. But it’s an abstraction that actually gives us numerical parameters describing how we behave. Just as a computer has memory and processor, so does our model of a human. Actually, the model has several different kinds of memory, and several different processors.

Input from the eyes and ears is first stored in the **short-term sensory store**. As a computer hardware analogy, this memory is like a frame buffer, storing a single frame of perception.

The **perceptual processor** takes the stored sensory input and attempts to recognize symbols in it: letters, words, phonemes, icons. It is aided in this recognition by the **long-term memory**, which stores the symbols you know how to recognize.

The **cognitive processor** takes the symbols recognized by the perceptual processor and makes comparisons and decisions. It might also store and fetch symbols in **working memory** (which you might think of as RAM, although it’s pretty small). The cognitive processor does most of the work that we think of as “thinking”.

The **motor processor** receives an action from the cognitive processor and instructs the muscles to execute it. There’s an implicit feedback loop here: the effect of the action (either on the position of your body or on the state of the world) can be observed by your senses, and used to correct the motion in a continuous process.

Finally, there is a component corresponding to your **attention**, which might be thought of like a thread of control in a computer system. Note that this model isn’t meant to reflect the anatomy of your nervous system. There probably isn’t a single area in your brain corresponding to the perceptual processor, for example. But it’s a useful abstraction nevertheless.

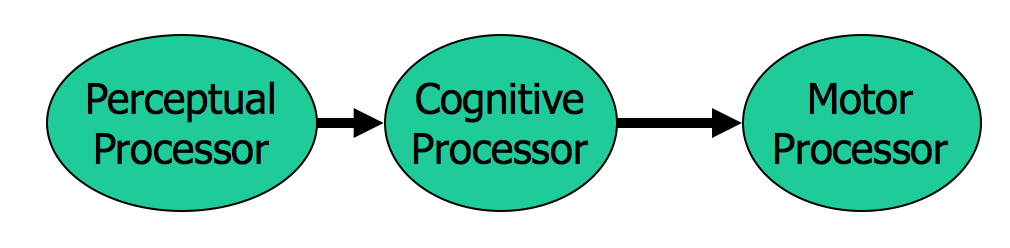

The main property of a processor is its **cycle time**, which is analogous to the cycle time of a computer processor. It’s the time needed to accept one input and produce one output.

Like all parameters in the MHP, the cycle times shown above are derived from a survey of psychological studies. Each parameter is specified with a typical value and a range of reported values. For example, the typical cycle time for perceptual processor, T_p, is 100 milliseconds, but various psychology studies over the past decades have reported mean cycle times between 50 and 200 milliseconds. The reason for the range is not only variance in individual humans; it also varies with conditions. For example, the perceptual processor is faster (shorter cycle time) for more intense stimuli, and slower for weak stimuli. You can’t read as fast in the dark. Similarly, your cognitive processor actually works faster under load. Consider how fast your mind works when you’re driving or playing a video game, relative to sitting quietly and reading. The cognitive processor is also faster on practiced tasks.

It’s reasonable, when we’re making engineering decisions, to deal with this uncertainty by using all three numbers, not only the nominal value but also the range.

One interesting effect of human perceptual system is **perceptual fusion**. Here's an intuition for how fusion works. Our perceptual processor runs at a certain frame rate, grabbing one frame (or picture) every cycle, where each cycle takes T_p seconds. Two events occurring less than the cycle time apart are likely to appear in the same frame. If the events are similar -- e.g., Mickey Mouse appearing in one position, and then a short time later in another position -- then the events tend to fuse into a single perceived event -- a single Mickey Mouse, in motion. Perceptual fusion is responsible for the way we perceive a sequence of movie frames as a moving picture, so the parameters of the perceptual processor give us a lower bound on the frame rate for believable animation. 10 frames per second is good enough for a typical case, but 20 frames per second is better for most users and most conditions. Perceptual fusion also gives an upper bound on good computer response time. If a computer responds to a user's action within T_p time, its response feels instantaneous with the action itself. Systems with that kind of response time tend to feel like extensions of the user's body. If you used a text editor that took longer than T_p response time to display each keystroke, you would notice. Fusion also strongly affects our perception of causality. If one event is closely followed by another -- e.g., pressing a key and seeing a change in the screen -- and the interval separating the events is less than T_p, then we are more inclined to believe that the first event caused the second. Perceptual fusion provides us with some rules of thumb for responsive feedback. If the system can perform a command in less than 100 milliseconds, then it will seem instantaneous, or near enough. As long as the result of the command itself is clearly visible -- e.g., in the user's locus of attention -- then no additional feedback is required. If it takes longer than the perceptual fusion interval, then the user will notice the delay -- it won't seem instantaneous anymore. Something should change, visibly, within 100 ms, or perceptual fusion will be disrupted. Normally, however, ordinary low-level feedback is enough to satisfy this requirement, such as a push-button popping back, or a menu disappearing. One second is a typical turn-taking delay in human conversation -- the maximum comfortable pause before you feel the need to fill the gap with something, even if it's just "uh" or "um". If the system's response will take longer than a second, then it should display additional feedback. For short delays, the hourglass cursor (or spinning cursor or throbber icon shown here) is a common design pattern. For longer delays, show a progress bar, and give the user the ability to cancel the command. Note that progress bars don't necessarily have to be accurate. (18.2% is actually preposterous -- who cares about 3 significant figures of progress?) An effective progress bar has to show that progress is being made, and allow the user to estimate completion time at least within an order of magnitude -- a minute? 10 minutes? an hour? a day?The cognitive processor is responsible for making comparisons and decisions.

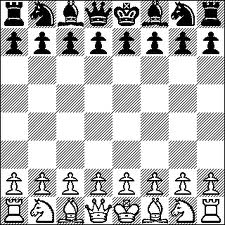

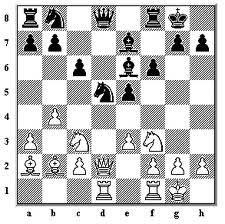

Cognition is a rich, complex process. The best-understood aspect of it is **skill-based** decision making. A skill is a procedure that has been learned thoroughly from practice; walking, talking, pointing, reading, driving, typing are skills most of us have learned well. Skill-based decisions are automatic responses that require little or no attention. Since skill-based decisions are very mechanical, they are easiest to describe in a mechanical model like the one we’re discussing.

Two other kinds of decision making are **rule-based**, in which the human is consciously processing a set of rules of the form if X, then do Y; and **knowledge-based**, which involves much higher-level thinking and problem-solving.

Rule-based decisions are typically made by novices or occasional performers of a task. When a student driver approaches an intersection, for example, they must think explicitly about what they need to do in response to each possible condition (“Is there a stop sign? Are there other cars arriving at the intersection? Who has the right of way?”). With practice, the rules become skills, and you don’t think about how to do them anymore.

Knowledge-based decision making is used to handle unfamiliar or unexpected problems, such as figuring out why your car won’t start.

We’ll focus on skill-based decision making for the purposes of this reading, because it’s well understood, and because efficiency is most important for well-learned procedures.

The motor processor can operate in two ways. It can run autonomously, repeatedly issuing the same instructions to the muscles. This is “open-loop” control; the motor processor receives no feedback from the perceptual system about whether its instructions are correct. With open loop control, the maximum rate of operation is one cycle every T_m ~ 70 ms.

The other way is “closed-loop” control, which has a complete feedback loop. The perceptual system looks at what the motor processor did, and the cognitive system makes a decision about how to correct the movement, and then the motor system issues a new instruction. At best, the feedback loop needs one cycle of each processor to run, or T_p + T_c + T_m ~ 240 ms.

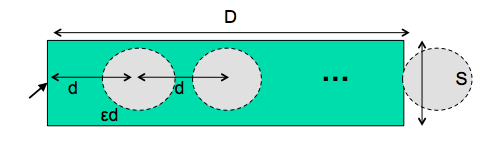

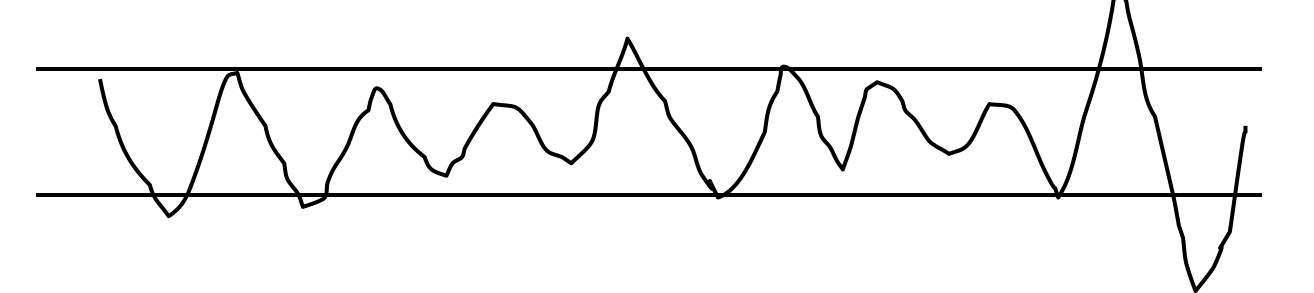

Here’s a simple but interesting experiment that you can try: take a sheet of lined paper and scribble a sawtooth wave back and forth between two lines, going as fast as you can but trying to hit the lines exactly on every peak and trough. Do it for 5 seconds. The frequency of the sawtooth carrier wave is dictated by open-loop control, so you can use it to derive your T_m. The frequency of the wave’s envelope, the corrections you had to make to get your scribble back to the lines, is closed-loop control. You can use that to derive your value of T_p + T_c.

[We already appealed](../05-Efficiency/#pointing-and-steering) to this model of closed-loop motor control to help explain why Fitts’s Law is logarithmic in distance and size, while the steering law is linear.

Simple reaction time – responding to a single stimulus with a single response – takes just one cycle of the human information processor, i.e., T_p+T_c+T_m.

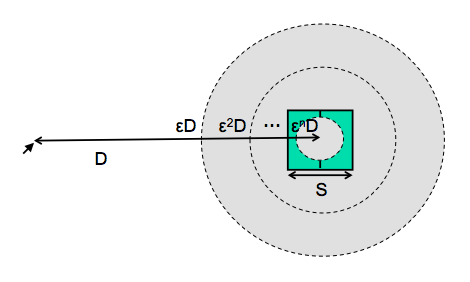

But if the user must make a choice – choosing a different response for each stimulus – then the cognitive processor may have to do more work. The Hick-Hyman Law of Reaction Time shows that the number of cycles required by the cognitive processor is proportional to amount of *information* in the stimulus. For example, if there are N equally probable stimuli, each requiring a different response, then the cognitive processor needs log N cycles to decide which stimulus was actually seen and respond appropriately. So if you double the number of possible stimuli, a human’s reaction time only increases by a constant.

Keep in mind that this law applies only to skill-based decision making; we assume that the user has practiced responding to the stimuli, and formed an internal model of the expected probability of the stimuli.

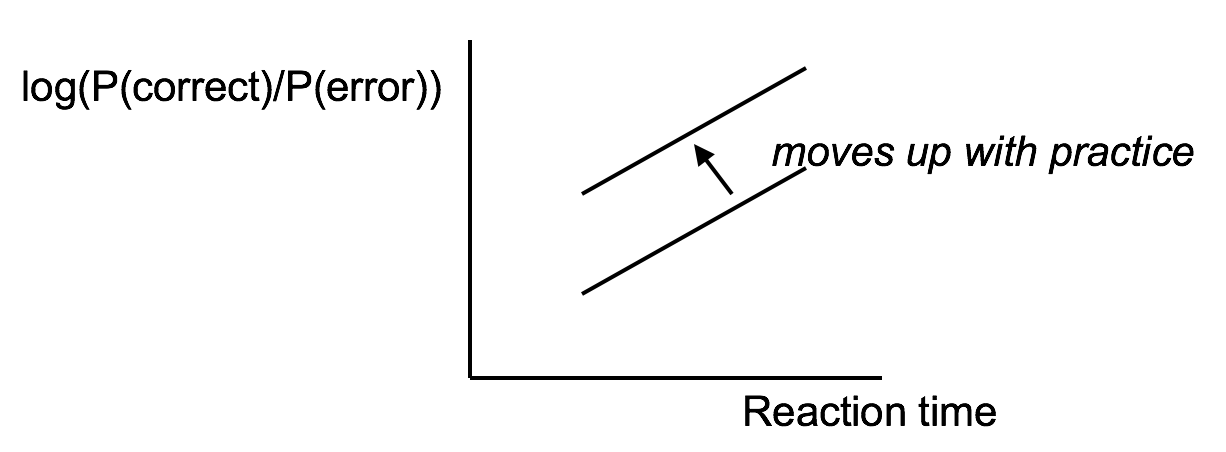

Another important phenomenon of the cognitive processor is the fact that we can tune its performance to various points on a **speed-accuracy tradeoff** curve. We can force ourselves to make decisions faster (shorter reaction time) at the cost of making some of those decisions wrong. Conversely, we can slow down, take a longer time for each decision and improve accuracy. It turns out that for skill-based decision making, reaction time varies linearly with the log of odds of correctness; i.e., a constant increase in reaction time can double the odds of a correct decision.

The speed-accuracy curve isn’t fixed; it can be moved up by practicing the task. Also, people have different curves for different tasks; a pro tennis player will have a high curve for tennis but a low one for surgery.

One consequence of this idea is that efficiency can be traded off against safety. Most users will seek a speed that keeps slips to a low level, but doesn’t completely eliminate them.

One more relevant feature of the entire perceptual-cognitive-motor system is that the time to do a task decreases with practice. In particular, the time decreases according to a power law. The power law describes a linear curve on a log-log scale of time and number of trials.

In practice, the power law means that novices get rapidly better at a task with practice, but then their performance levels off to nearly flat (although still slowly improving).

**Steering Law**

**Steering Law**